Free expression online

Online Safety Act: A Guide for Organisations Working with the Act

This document is intended as a full overview of the Online Safety Act (OSA, or the Act) and how it works for organisations attempting to understand it and its implications. We explain the OSA’s key regulatory provisions as they impact moderation decisions and practices and its knock-on effect on the rights and freedoms of Internet businesses and users. For the enforcement mechanisms available to Ofcom see our detailed analysis of the problems the Act creates, published alongside this guide.

The Online Safety Act 2023 is a complex piece of legislation that places extensive duties on Internet service providers regarding content moderation, transparency reporting, and age verification. It also creates new criminal offences in respect of online communication. In this section we highlight these new key duties and offences.

Part 3 of the Act imposes duties on regulated user-to-user and search services. A user-to-user service is defined broadly as any service “by means of which content that is generated directly on the service by a user of the service, or uploaded to or shared on the service by a user of the service, may be encountered by another user, or other users, of the service” [Section 3(1)]. Email services, one-to-one aural communication platforms like Skype, messaging platforms that share content between telephone numbers like WhatsApp, and user-review sites like Trustpilot are excluded as long as the service provider does not use them to supply pornographic content. Similarly, workplace platforms set up internally within public or private organisations are excluded, as are education and childcare platforms [Schedule 1]. A search service is regulated if it searches multiple websites or databases rather than a single site or database [Section 229].

Regulated services need not be based in the UK but must have “links” with the UK, either because they have a “significant number” of UK users, or they view the UK as a target market, or that they can be accessed from the UK and there “are reasonable grounds to believe that there is a material risk of significant harm to individuals” in the UK from their content [Sections 4(2), 4(5), 4(6)].

All services that meet this broad description are regulated. This means, for instance, that a website hosting a forum that enables users to share content is potentially in scope and must comply with the general duties imposed by the OSA. Yet there are thresholds above which the Act applies particular additional duties.

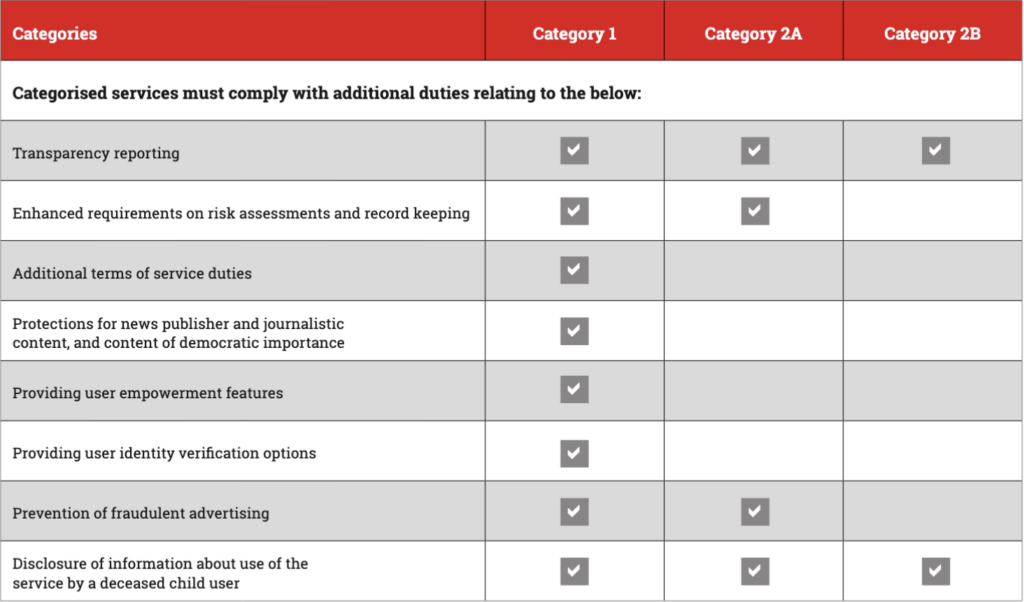

These depend on secondary legislation. Regulated services will be classified into one of three categories for the purposes of assigning their duties. User-to-user services – social media – are classed as Category 1 or Category 2B, depending on their size, functionality, and other features. Category 2A services are large search engines.

The additional duties imposed on each category are outlined in the table below:

Table 1: Categorisation and duties, from Ofcom’s report of March 2024 entitled ‘Categorisation: Advice Submitted to the Secretary of State’, p.4. See also sections 94 and 95 OSA.

The threshold conditions may change for these categories, as the legislation is open-ended and designed to allow changes over time. In preliminary research and advice as of March 2024, Ofcom recommended that Category 1 user-to-user services should be regarded as any service that uses a content recommender system and has more than 34 million UK users (half the population), or that uses a content recommender system, allows users to forward or share user-generated content, and has more than 7 million UK users (10% of the population). Similarly, a category 2A search engine has more than 7 million UK users. A category 2B user-to-user service allows users to send direct messages and has more than 3 million UK users (5% of the population). Services that fall below these thresholds, if they are adopted, will still have to comply with the duties the Act imposes on all services, but will not have to perform the additional requirements.

However, charities from the mental health and children’s sectors are lobbying the new Labour government to lower the threshold to bring even small websites within the scope of the Act.

The duties imposed by Part 3 are the OSA’s key regulatory elements. They are designed to make regulated services do the bulk of the work, rather than tasking Ofcom with policing all services in detail. Instead, all regulated services will perform mandatory self-assessments in line with the general regulatory framework. They must implement appropriate measures in response to their own findings, in line with guidance and Codes of Practice prepared by Ofcom for the Secretary of State and laid before Parliament as secondary legislation. Ofcom will supervise their implementation, in practice focusing on the larger, categorised services.

Risk assessments are the critical device in Part 3. All regulated services must produce risk assessments in relation to specified categories of content and behaviour on their platform and keep those assessments up to date. Changes to their systems and Terms of Service cannot be made without first updating the relevant risk assessment. Transparency requirements are intended to ensure that Ofcom can review the relevant measures and assess overall compliance.

Where necessary, Ofcom can intervene directly, and extensive enforcement powers are available to it when services and individual senior managers fail to comply. Ideally, however, Ofcom will simply ensure compliance with the mandatory requirements. Ofcom plays a meta-regulatory role, co-ordinating best practices in a manner explicitly intended to develop and evolve iteratively across the sector in response to its own operations.

Part 3 places the following duties on all regulated user-to-user services, whether category 1 or 2B:

- duties about illegal content risk assessments set out in section 9,

- duties about illegal content set out in section 10(2) ‘to ‘(8),

- a duty about content reporting set out in section 20,

- duties about complaints procedures set out in section 21,

- duties about freedom of expression and privacy set out in section 22(2)and ‘(3), and

- duties about record-keeping and review set out in section 23(2) ‘to ‘(6).

All regulated user-to-user services that are “likely to be accessed by children” have additional duties:

- duties to carry out children’s risk assessments under section 11,

- duties to protect child safety online under section 12.

Category 1 services (large user-to-user platforms) have the following additional duties:

- a further duty regarding illegal content risk assessments set out in section 10(9),

- a further duty about children’s risk assessments set out in section 12(14),

- duties about assessments related to ‘adult user empowerment’ set out in section 14,

- duties to empower adult users set out in section 15,

- duties to protect content of democratic importance set out in section 17,

- duties to protect news publisher content set out in section 18,

- duties to protect journalistic content set out in section 19,

- duties about freedom of expression and privacy set out in section 22(4), ‘(6) ‘and ‘(7), and

- further duties about record-keeping set out in section 23(9) ‘and ‘(10).

We now briefly explain each category of duty, in turn.

This duty requires all regulated platforms to assess the risk that illegal content or behaviour will be published or carried out using their services. This is a broad category, but in practice there are specific “priority” categories that require close attention: terrorist content, child sexual exploitation and abuse material (CSEA), and 39 other kinds of wide-ranging priority content listed in Schedule 7, including assisting suicide, public order offences of causing fear of violence or provoking violence, harassment, stalking, making threats to kill, racially aggravated harassment or abuse, supplying drugs, firearms, knives, and other weapons, and facilitating “foreign interference” in the UK’s public affairs under the National Security Act 2023.

Risk assessments must factor in the user base, algorithms used in recommender systems and moderation systems, the process of disseminating content, the business model, the governance system, the use of any “proactive” technology (defined in section 231 as content identification, user profiling, or behaviour identification technologies), any media literacy initiatives, and any other systems and processes that affect these risks. To this end, Ofcom will provide “risk models” as guidance that will set out baseline factors to consider. All Category 1 services must publish a summary of their most recent risk assessment.

Risk assessment must in turn feed into the design and implementation of proportionate measures, applied across all relevant elements of the design and operation of the regulated service or part of the service, to prevent users encountering priority illegal content and mitigate and manage the risk that the service may be used to commit a priority offence. The risks of harm from illegal content identified in the most recent risk assessment must be minimised by implementing proportionate systems and processes that minimise the length of time that illegal content is present and allow it to be swiftly taken down once notified of its presence. Services must also act in respect of their compliance arrangements, their functionalities and algorithms, their policies and terms of use and blocking users, content moderation policies, user control options, support measures, and internal staff policies. Measures including the use of proactive technology may be applied, and services must spell such measures out to users in clear and accessible policies and terms of service. Measures to take down or restrict illegal material must be applied consistently.

We expand on illegal harm duties further in Part 3 below.

The same model of self-assessment and response applies to risks relating to child safety for all social media and search services “likely to be accessed by children”. Risk profiles must pay heed to the user base, including different age groups of child users; each kind of “primary priority content” harmful to children; each kind of priority content; and “non-designated content”/ This all puts an additional onus on services to consider potential harms not specified by either legislation or regulator.

As with illegal content, services must assess the levels of risk presented by each category of content, having regard to its specific functions, algorithms, and use characteristics. The legislation specifically includes consideration of any functions that enable adults to search out and contact child users. For each element, the service must consider “nature, and severity, of the harm that might be suffered by children” (s11(g)), and how the design, operation, business model, governance, use of proactive technology, media literacy initiatives and “other systems and processes” may reduce or increase these risks. Again, these rather open-ended criteria are to be fleshed out by model risk profiles that are to be created and updated over time by Ofcom.

Section 12 creates a duty to mitigate and manage the risks identified by the assessment in a proportionate manner. Sections 60 and 61 divide content harmful to children into three broad headings: “Primary Priority Content” (PPC), “Priority Content” (PC), and Non-designated content (NDC).

PPC is non-textual pornographic content and any content that encourages, promotes, or provides instructions for suicide, self-harm, or eating disorders.

PC includes several broad categories:

- Abusive content, or content which incites hatred, on grounds of race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or gender reassignment;

- Bullying content;

- Violent content which encourages, promotes, or provides instructions for a serious act of violence against a person, or which graphically depicts real or realistic serious violence against a person, animal, or fictional creature;

- Harmful substances content that encourages taking or abusing harmful substances or substances in a harmful quantity;

- Dangerous stunts and challenges content.

NDC is any other content “which presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of children in the UK”.

Of particular note is section 12(3), which stipulates that children of any age must be prevented from encountering “primary priority content” that is harmful to children. Section 12(3) OSA requires all regulated user-to-user services that are “likely to be accessed by children” to use “proportionate systems and processes” to prevent children from encountering primary priority content that is harmful to children, including pornographic content, except where such content is prohibited on the service for all users.

Section 12(4) requires the use of highly effective age assurance measures to prevent children encountering PPC on a service except where PPC is prohibited for all users. Age assurance is not mandated for user-to-user services except in relation to PPC, but it is listed as a potential measure for proportionately addressing other duties to children.

Section 29(2) requires search services take “proportionate measures” to mitigate and manage the risk and impact of harm to children by search content. Large general search engines should apply safe search settings that filter out PPC for all users believed to be children. Users should not be able to switch this off.

By contrast, children must be protected from the risk of encountering “priority content that is harmful”. This is defined at section 62 as including content abusive on grounds of race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability or gender reassignment, or content which incites hatred on the same grounds. It also includes content that encourages or instructs “an act of serious violence against a person”; “bullying content”; the graphic depiction of a realistic injury or realistic violence against a real or fictional person, animal, or creature; content encouraging or instructing people to perform dangerous stunts and challenges; and content that encourages a person to ingest, inject, inhale, or otherwise take a harmful substance. Bullying content is defined as content targeted against a person that conveys a serious threat, is humiliating or degrading, and is part of a “campaign of mistreatment”. The categories of harmful content are deliberately intended to be iterative and mutable – section 63 requires Ofcom to review the incidence of such content and the severity of harm that children suffer, or may suffer, as a result and produce advisory reports no less than once every three years with recommended changes.

All these categories of harmful communication must be operationalised via the content moderation systems used on all regulated services that children can access. The duty to prevent any encounter with primary priority content, however, leads logically to section 12(4), which requires the implementation of age verification or age estimation systems. According to section 12(6), age verification or estimation systems must be “highly effective at correctly determining” whether a user is a child or an adult.

In the initial Online Safety White Paper, the government proposed a requirement for regulated services to assess and manage the risks to all users from “legal but harmful” communication. Such a measure would have imposed blanket censorship for all users, regardless of their subjective preferences, in the name of politically-defined population-level “harms”. During the Act’s passage through Parliament these censorious provisions were replaced with “user empowerment” duties, which require Category 1 services to enable individual users to select what kinds of content gets filtered out of their online experience.

Section 14 “assessments related to adult user empowerment” must include considering the “likelihood” (arguably a synonym for risk) that users will encounter different kinds of “relevant content”, including the likelihood of “adult users with a certain characteristic or who are members of a certain group encountering relevant content which particularly affects them” [Section 14(5)(d)]. Then proportionate measures must be taken to give adult users the ability to filter out “relevant content”, self-referentially defined at section 15(2):A duty to include in a service, to the extent that it is proportionate to do so, features which adult users may use or apply if they wish to increase their control over content to which this subsection applies. Section 16 holds that such content includes anything that encourages, promotes, or gives instructions on suicide, self-harm, or eating disorders (s16(3)). It includes anything that is “abusive” in relation to race, religion (or lack thereof), sex, sexual orientation, disability, or gender reassignment, and anything that incites hated against people of a particular race, religion, or sexual orientation, anyone with a disability, or anyone with the characteristic of gender reassignment, meaning “the person is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person’s sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex”. This definition is thus a subset of the list of priority content deemed harmful to children. But whereas it applies by law to all services on which children may be present, it only applies to adults who self-select and therefore avoids the complex questions of freedom of expression that would otherwise arise.

Category 1 services (large social media platforms) must offer features that reduce the likelihood of users encountering “relevant” content, or that alert them if such content is present on the site. Users must also be enabled to block all non-verified users – people who have not confirmed their real identity to the platform – from contacting them or from uploading content that they may encounter. Related, all Category 1 services must offer adult users the option to verify their identity.

In practice, this amounts to an “opt-in” version of the curtailment of “legal but harmful” content. To provide this, Category 1 platforms will have to use automated semantic analysis and user-driven reporting systems to identify such content so that the filters work effectively. The key priority for services – and users – is that their filtering systems accurately do what they purport to do with a proportionate degree of reliability. While services likely take these steps anyway in the course of moderating content, the state’s imposition of such a requirement is an interference with their freedom of expression as private companies.

Section 17 places a general duty on all services to use “proportionate systems and processes to ensure that the importance of the free expression of content of democratic importance is taken into account” in respect of taking content moderation action or acting against a user, whether a warning, suspension, or ban, for generating or sharing such content. Such measures must apply “in the same way to a wide diversity of political opinion” (s17(3)). Although a “wide diversity” of opinion is not defined, it implies that some political opinions do not count as democratically important.

At section 17(7), content of democratic importance is defined as news publisher content or user-generated content that “is or appears to be specifically intended to contribute to democratic political debate in the UK or a part of area of the UK”.

Section 18 creates a prospective duty to protect “news publisher” content by imposing steps that must be taken before action can be taken to moderate or remove content or user accounts from news media organizations. First, notice must be given of the intended action, along with reasons and an account of how the specific duty to protect news content was considered. A reasonable period for representations must be allowed, then a considered decision must be given with reasons. These steps can only be skipped where there is a “reasonable consideration” that the material would incur criminal or civil penalties, with the publisher then entitled to retroactively appeal. Clear and accessible descriptions of these provisions must be included in the Terms of Service.

This provision was added following lobbying by the British press. Ironically, they themselves, especially the tabloid papers, have historically been responsible for promoting content that might meet the criteria of harmful or even illegal, yet their political power is such that they successfully campaigned for special treatment in the OSA to mitigate the risk of losing readership, ad revenue, and reputational integrity through moderation action taken against their social media posts. Consequently, the press has ended up with much better procedural protections than ordinary citizens.

Section 19 applies a similar duty to protect UK- linked “journalistic content”, which includes content for the purpose of journalism, even if the producer is not a journalist by profession. Rather than giving advance notice, however, services must create a dedicated expedited complaints procedure to allow users to appeal against the removal of any content, or any action taken against them, with swift reinstatement when complaints are upheld.

Section 22 imposes a duty to have regard “to the importance of protecting users’ right to freedom of expression within the law”. This means that, when deciding on and implementing safety measures and policies, services must have “particular regard” to the “importance of protecting users from a breach of any statutory provision or rule of law concerning privacy that is relevant to the use or operation of a user-to-user service (including, but not limited to, any such provision or rule concerning the processing of personal data)”.

However, for reasons set out above regarding the mechanics of moderation, and in light of the extensive illegal harm and children’s duties discussed above, it is unlikely that such measures will be operationalised with any real impact.

All of this is part of the auditing processes mandated by the OSA. Category 1 services must produce impact assessments on how their safety measures and polices will affect freedom of expression and privacy, with particular information on news publisher and journalistic content. They must keep the assessment updated and specify positive steps they are taking in response to identified problems.

There is a duty imposed at s20 to create systems for users and/or affected others to easily report illegal content or content harmful to children on a service that children can access. The affected person must be in the UK and the subject of the content, or of a class of people targeted, or a parent, carer, or adult assistant who is the subject of the content.

At section 21, there is a duty to take “appropriate action” in response to complaints that are relevant to the duties imposed by the Act. The complaints and response process must be accessible, easy to use, and transparent in its effects, including child users. This also includes complaints about the way the service uses proactive safety-oriented technology such as algorithmic classifiers. Section 23 creates record-keeping and review duties that apply to all risk assessment duties.

The duties discussed so far apply to “user-to-user” social media. Sections 24-34 OSA reproduce several of these duties in respect of search engine services. Search engines are not required to verify the age of users and or comply with user empowerment duties, but they must take proportionate measures to mitigate and manage the risks of harm from illegal content and content harmful to children, including minimising (but not absolutely preventing) the risk that children might encounter primary priority content harmful to children. There are similar duties in respect of content reporting, complaints, freedom of expression and privacy, and record-keeping and review (see section 24).

Under Part 5 of the OSA, and expressly under section 81, services that publish or display pornographic content have a duty to implement “highly effective age assurance” (referred to in draft guidance as HEAA) to ensure that “children are not normally able to encounter pornographic content” on the service. This means that the method chosen has to be highly effective in principle, and that it has to be implemented in a manner that is highly effective.

This overlaps with section 12 duties in respect of harm to children. As explained above, all content harmful to children is regulated by Part 3 of the OSA, and expressly includes pornographic content (other than purely textual content) as “Primary Priority Content” (PPC), ranking it alongside any content that encourages, promotes, or provides instructions for suicide, self-harm, or eating disorders. In respect of PPC, child users must be “prevented” from access, rather than merely “protected” from the risk of encountering it. Firm age-verifying gateways around pornographic content on specific porn sites are, in other words, doubly mandated by the OSA. The duplication may be explained by the fact that there is no minimum number of users required for the provisions of Part 5 to bite. Any site that provides pornographic content and that has a “significant” number of UK users or that targets the UK market is caught by the OSA, meaning that even small niche providers of pornographic content are required to implement HEAA measures.

Where a user is deemed to be a child by a regulated user-to-user site, three types of safety measure can be applied, depending on its profile: first, access controls that prevent access to the service or part thereof; second, content controls that protect children from encountering harmful content; and finally, measures that prevent recommender systems from promoting the site’s harmful content to children.

The question of which method should apply depends on is the type of service provided and the risk level it presents:

- In relation to access to the service, strong age assurance gatekeeping must apply to all user-to-user services that principally host or disseminate Primary Priority Content or Priority Content. Access must be entirely controlled by HEAA, meaning users must somehow show that they are over-18 in order to gain access to any user-to-user service that focuses on pornography, suicide and self-harm, or eating disorders.

- In relation to content controls, where disseminating PPC and PC is not the principal purpose of the service, but the service does not prohibit such content, and (in respect of PC) where the service is rated as a high or medium risk for hosting PC, HEAA must apply to content control measures to ensure that children who access the service, or indeed any user who does not demonstrate that they are an adult, are protected from encountering it via content filtering methods. This would apply to any social media service that tolerates user-generated and promoted pornography, like X (formerly known as Twitter), where accounts advertising pornographic material are not banned.

- User-to-user services that operate recommender systems to select and amplify content, and which is rated high or medium risk for PPC or PC (excluding bullying) must use HEAA methods to control the recommender system settings.

- Other relevant differences in the services provided to children and adults include private messaging settings, the ability to search for suicide, self-harm, and eating disorder content, and signposting users to sources of support, amongst other design features aimed at minimising the risk of harm to children.

In effect, to provide a fully uncensored service hosting lawful social media content intended for adult users who do not mind encountering pornographic, violent, or other controversial material even if that material is not the reason for most users’ interest in the service, such platforms must still estimate or verify that their users are adults. Age assurance unlocks the adult versions of regulated user-to-user services:

- Access to services that exist to host and disseminate PPC

- Content controls allowing access to identified PPC/PC on other services

- The absence of content moderation measures to identify and filter PPC/PC

- Recommender systems that recommend PPC/PC

We explore the practicalities of this in the main report.

Besides provisions designed to combat online fraud propagated by regulated services, the Act creates several new communication offences. Aside from enabling the arrest and prosecution of individuals, these provisions broaden the scope of “illegal content and behaviour” and the associated risks of encountering it on regulated services. Therefore, they are an extension of the new mandated regime of moderation requirements. Regulated services must take steps to mitigate the risk of these offences or risk failing to comply with their duties. The new offences are:

S 179 False communications offence

It is an offence to send, without reasonable excuse, a message one knows to be false if it is intended to cause “non-trivial psychological or physical harm to a likely audience”. A “likely audience” is anyone who can be reasonably foreseen to encounter the message. It need not be a specific person.

S 181 Threatening messages

It is an offence to send a message by any medium conveying a threat of death or serious harm with the intention to cause fear that it will be carried out, or where the sender is reckless as to the effect. The message need not be directly sent to the victim provided that it is communicated such that they may “encounter” it – for instance, posting it to a social media site or message board.

S 183 offences of sending or showing flashing images electronically

It is an offence to send messages, or cause messages to be sent, containing flashing images to a person known to have, or believed to have, epilepsy with the intention that they see the images and are harmed by them.

S 184 Offence of encouraging or assisting serious self-harm

It is an offence to intentionally encourage or assist another person to cause serious self-harm, whether in person or online. “Serious” means acts that cause the equivalent of grievous bodily harm and includes successive acts of less severe self-harm that cumulatively cross the threshold. These offences apply to acts done outside the UK provided D is habitually resident or incorporated in the UK.

S 187 Sending photograph or film of genitals

This provision criminalizes “cyberflashing” – that is, intentionally sending or giving a photograph or film of any person’s genitals to another, if doing so is intended to cause the recipient alarm, distress or humiliation, or if the sender obtains sexual gratification regardless of the recipient’s response.

S 188 Sharing or threatening to share intimate photography or film

This provision modifies the Sexual Offences Act 2003 to make it an offence to share or threaten to share intimate images or videos depicting another person in exemption for children or those without capacity if shared for medical purposes, and exemptions for images ordinarily shared between family members.