Immigration, Data and Technology: Needs and Capacities of the Immigration Sector

This report is based on the findings of a survey launched earlier this year with Privacy International to identify the needs and capacities of migrants’ rights organisations to respond to data, privacy and the use of new technologies. It details our findings and recommendations on how to increase the capacity of the migrants’ rights sector and areas for future work.

ABOUT ORG

Open Rights Group (ORG) is a UK based digital campaigning organisation working to protect fundamental rights to privacy and free speech online. With over 3,000 active supporters, we are a grassroots organisation with local groups across the UK.

Our work on data protection and privacy includes challenging the immigration exemption to UK data protection law, defending the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) from attempts to water down its provisions, and challenging uncontrolled and unlawful data sharing by online advertisers.

Open Rights Group would like to thank Unbound Philanthropy for the support to produce this report and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation for the support to take these ideas forward. We would also like to thank Yva Alexandrova Meadway for her work on this report and the early part of the Immigration and Digital Rights project.

openrightsgroup.org

KEY FINDINGS

The main priority areas for the sector, based on the survey responses are:

- building the capacity of NGOs to better support their clients

- building the evidence base and documenting harms and lived experiences of migrants to engage in policy-making and

- building the capacity of NGOs to raise awareness among the general public, national and international fora, and engage in successful advocacy.

Types of support needed:

- Trainings;

- Information sheets on rights, risks and how to counter them;

- Policy briefs on data protection and the obligations of government and the private sector; and

- Support for advising clients on their digital rights and how to safeguard them.

Main issues encountered:

- Disproportionate data collection

- Use of data for purposes other than it was originally given for

- Automated decision-making was the least frequently encountered issue, but was the most concerning emerging issue

1 IMMIGRATION, DATA AND TECHNOLOGY – THE WIDER POLICY CONTEXT

Migration is a process that still takes place very much in the real world: people cross physical borders, they travel thousands of miles, swim in ice cold water, sit in crammed lorries, and live in camps often with little protection from nature. Increasingly, however, technology is becoming an essential part of their journeys, they use mobile technologies and social media to stay in touch with their families and friends, establish contacts to plan their journeys, stay updated about changes on their routes. Upon arrival they use social media to find support in communities, as well as to find work, start a process of integration and stay in touch with their homes and families.

At the same time, governments are also increasingly using technology to control migration. In the UK the Home Office has hugely expanded its use of data in immigration as part of the introduction of the “hostile environment” policy introduced by the Conservative government, which made a commitment made during the 2010 general election to reduce immigration to the tens of thousands, as well as to reduce irregular migration. As part of this policy, requirements were put on public servants – such as GPs, teachers, welfare advisors, local councillors, MPs and private actors – such as landlords, banks and building societies to check the immigration status of individuals and families using their services. Through a web of data sharing agreements they are obliged to share the personal data they collect on their service-users with immigration officials at the Home Office who may use that data for the purpose of immigration enforcement, including detention and deportation.[1]

The fusion within the Home Office between the hostile environment policy and existing forms of institutional racism led to the biggest immigration scandal in recent times – Windrush. Hundreds, possibly thousands of legal UK residents, who came in the 50s, 60s and 70s from the Caribbean, were misclassified as illegal immigrants and were denied healthcare, employment, pensions, then detained and deported. The Home Office first destroyed their original arrival cards and then demanded documentary proof of their arrival. The data that the Home Office maintains is full of gaps, which has meant that it is still unknown how many people have had their personal data shared with the Home Office by employers, local councils, GPs and how many of them have been subjected to immigration enforcement under the hostile environment measures. The March 2020 Wendy Williams Independent Review[2] offers a forensic analysis of the causes of the Windrush scandal, including the poor quality of data used by the Home Office.

The new “immigration exemption” introduced in the 2018 Data Protection Act is another way in which immigration and data protection collide. The exemption in Schedule 2 Part 1 Paragraph 4 of the Data Protection Act 2018 removes data protection rights for those subject to immigration enforcement. A legal challenge brought by ORG and The 3 million argued that removing data rights protected by GDPR prevents individuals from knowing whether the information held about them is accurate and that the exemption, used by the Home Office to deny people access to their personal data, is far too broad and imprecise. As part of the proceedings, the Home Office was also forced to reveal that it had used the exemption in 60% of immigration-related requests for data.[3] The challenge was overthrown by the High Court but an appeal has been granted and will take place in February 2021.

Brexit and the new Immigration Bill going through Parliament as of November 2020 will bring an end to the right to free movement for EU citizens in the UK and will change their migration status. Despite assurances that the new Settled Status scheme will protect their existing rights to reside, work, study and access services in the UK, there are concerns that over 3 million people will become subject to the hostile environment policy that has plagued the lives of other migrants in the UK once the Transition Period ends in June 2021.

Finally and most recently, the Covid-19 pandemic has driven an increased focus on technologies – contact tracing apps, electronic tags and immunity passports have been discussed or developed with varying degrees of success. These technologies are the subject of wider debates about technology and privacy that are strongly interlinked with discussions of the wider impact that new technologies have on marginalised and socially excluded people who are worried about sharing their personal data with the government. Directly, these concerns affect people whose immigration status may be irregular, such as undocumented migrants and individuals whose visas have expired, failed asylum seekers receiving Section 4 support, people with no recourse to public funds (NRFP), or asylum seekers who are appealing a decision, people awaiting visa extensions, or others who may be in a legal limbo. Indirectly, these concerns may also affect a much wider set of people who have every legal right to be here but simply do not trust the Home Office with their personal data. The lack of adequate legal safeguards for such people makes requiring widespread use of such technologies risky.[4]

These developments are not confined to the immigration space. Policies are often trialled in the area of immigration as it is considered politically low risk. However, the Windrush inquiry and the immigration exemption litigation have clearly shown the links between immigration and other spheres of life and that attempts to limit the fundamental data protection rights of migrants have broader societal implications. As Liberty’s Gracie Bradley wrote in Runnymede’s recent report “To understand the full scale of its societal impact, we should also understand the hostile environment as a set of state practices of social sorting and exclusion that could be applied to groups well beyond those believed to be undocumented migrants. And we must also understand the technological capabilities that make this possible.”[5]

Against this backdrop of creeping digitisation, data sharing and algorithmic decision-making, Open Rights Group with the support of Unbound Philanthropy and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation is engaging in an effort to support organisations in the migrant and refugee sector to become better equipped in dealing with data and privacy issues, to better understand new technologies and their impact on immigration policy and to become better able to support their clients. This report is an attempt to summarise the existing capacities, and identified needs and to lay out suggestions on next steps.

2 SURVEY OVERVIEW

The Migration sector – needs and capacity assessment survey[6] was developed jointly by Open Rights Group and Privacy International and was shared among organisations in the wider migrant and refugee sector on an online platform between 16 April and 2 June 2020. The survey comprised 22 questions covering background information on the organisations and a range of themes on intrusive data processing, knowledge and use of data, privacy and technology and the relationship between these and the rights of migrants and refugees. It also asked about existing capacities, knowledge and use of tools, needs, priorities and future collaboration. It should be noted, that the numerical values of respondents used throughout this paper should be read more as an indication of where organisations’ relative standing rather than as a fixed numerical category. All the data in the tables and charts in this paper have been taken from the survey responses.

The survey received a total of 30 responses, which represented 19 organisations (providing 21 responses as in 3 cases there were two respondents from the same organisation)[7], 1 individual expert and 6 anonymous responses.

In terms of the core mandate of respondents: 12 organisations engaged in direct service delivery, 11 engaged in policy and/or advocacy, 11 involved in community support, 9 providing legal advice and 8 campaigning[8].

Organisations that responded cover nearly all existing categories of client groups including asylum seekers, refugees, migrants, EU citizens, people with no recourse to public funding (NRPF), as well as community and BAME groups.

The issue areas of work for respondents include[9]:

legal advice 14,

access to public services 18,

health 4,

education 13,

housing 10,

employment and working conditions 12, migrant voice and participation 9

In addition there were respondents working on: EU citizens’ rights under the Withdrawal Agreement; community cohesion; and integration and mental health. Four were specialised medical organizations.

Five of the responding organisations were located outside of London; their answers provide important insight into the needs and capacities existing in the rest of the country.

ORG is immensely thankful to all the respondents who took their time to answer the survey, despite the quite often serious strain on their resources. The number and types of respondents that filled the survey represent a good cross-section of organisations and their needs and abilities to work on data and immigration. As such, they offer a good basis for a discussion on how best to support and empower them in this work.

3 MAIN SURVEY FINDINGS

Below, we present and discuss the main findings of the survey. The different sections look at the existing organisational capacities, the main technologies and data protection practices and capacities to engage with them; the main concerns in the area of data collection and sharing and new technologies and practices; respondents’ experience and engagement with the main data protection tools; and ends with existing needs and priorities.

3.1 Capacity

In terms of existing capacities in the sector, it is indicative that two thirds of responding organisations have not received any training on data protection in terms of either their policy and advocacy, in relation to their clients’ privacy and data protection rights or on how to make use of data rights. Of those who did receive training it was mostly on GDPR. Providers of legal advice were among those who had received training on a regular basis. Of the six organisations working outside of London only one had received half a day’s training, organised by the council.

The table below shows how respondents rate their own capacity to work provide advice to clients, conduct research, undertake advocacy work, and campaigning. Most respondents rate their capacity as either non-existent or limited, while only individual organisations consider their capacities to be good or excellent. Providing technical advice to clients seems to be the most challenging for the majority of respondents – 25 said they had either non-existent or limited capacity and only 5 respondents had moderate, good or excellent.

Table 1. How would you rate your current capacity on topics of data exploitation and surveillance in the migration sector

| NON-EXISTENT | LIMITED | MODERATE | GOOD | EXCELLENT | |

| In providing technical advice to clients/beneficiaries | 37% 11 | 47% 14 | 10% 3 | 3% 1 | 3% 1 |

| To develop evidence/research | 33% 10 | 37% 11 | 17% 5 | 13% 4 | 0% 0 |

| To undertake advocacy | 30% 9 | 47% 14 | 7% 2 | 13% 4 | 3% 1 |

| In communicating and campaigning to the public | 27% 8 | 50% 15 | 13% 4 | 7% 2 | 3% 1 |

Addressing privacy issues is in line with the mandate of approximately 13 respondents, while 17 consider it completely outside or only slightly within their mandate showing that there may be more than capacity issues behind organisations’ ability to engage on this.

Table 2. To which extent your organisation considers addressing excessive use of data and new technologies as part of your mandate

| NOT AT ALL | SLIGHTLY | MODERATELY | EXTREMELY |

| 20% 6 | 37% 11 | 20% 6 | 13% 4 |

In addition, only a few organisations have had clients with direct experience or need of support in terms of their privacy. As a result many are not looking into this issue yet. Were such issues to arise, or were organisations to engage with this proactively, 80% of responses (24 organisations) would need additional resources, including funding, staff and training. Only six said they would not need additional resources.

It emerges that despite the existing broad understanding of the connection between immigration, data and new technologies, there exists the need to continue working on increasing awareness, as data sharing and other technologies continue to be developed and deployed by the Home Office. There is also space for providing support to help organisations better understand how this work relates to their existing mandates and how it may relate to work they are already doing. For service providers, there also seems to be a gap in the experience of clients. This may be due to the fact that data privacy is not among the main concerns but also could be due to an inability of service providers to spot data and privacy issues due to their lack of training.

3.2 Main issues

The survey covered a number of questions designed to capture the level of understanding and engagement on some of the key areas of concern such as intrusive data processing, the use of new technologies and practices.

In terms of the main issues around abusive and intrusive data processing practices, the results show that over half of respondents are concerned about disproportionate data collection and the use of data for other purposes than it was originally given for, followed closely by concerns about disproportionate data sharing and clients not having access to their data. Automated decision-making was mentioned by eight respondents, showing that this is still not an issue that the majority of organisations are encountering. There is currently no official Home Office decision-making policy using algorithmic (or automated) decision-making. However there are concerns that this will change for asylum-related decision making, as well as the recently abandoned visa screening algorithm.[10]

Table 3. Observed or known abusive/intrusive data processing practices

| YES | NO | |

| Disproportionate data collection | 60% 18 | 40% 12 |

| Disproportionate data sharing | 57% 17 | 43% 13 |

| Data being used for purposes other than what they were given for | 60% 18 | 40% 12 |

| Clients not having access to their data | 53% 16 | 47% 14 |

| Use of automated decision-making | 27% 8 | 73% 22 |

However, in terms of concerns about the use of new technologies –

automated decision-making was mentioned as the primary concern among respondents, followed by searching of mobile devices, social media monitoring[11] and facial recognition.[12] Almost all respondents expressed concern about one or all of the above issues.

Table 4. How concerned are you about these issues and the implications for the rights of migrants?

| EXTREMELY CONCERNED | VERY CONCERNED | MODERATELY CONCERNED | SLIGHTLY CONCERNED | NOT AT ALL | |

| Facial recognition | 30% 9 | 30% 9 | 23% 7 | 10% 3 | 7% 2 |

| Search of mobile devices | 40% 12 | 30% 9 | 17% 5 | 10% 3 | 3% 1 |

| Social media monitoring | 33% 10 | 33% 10 | 27% 8 | 3% 1 | 3% 1 |

| Use of automated decision-making | 40% 12 | 33% 10 | 17% 5 | 0% 0 | 10% 3 |

Concerns about technology use have also been raised regarding the use of video-conferencing for asylum interviews and location tracking of the pre-paid ASPEN cards that provide asylum-seekers with financial support.

Privacy concerns were also mentioned in relation to the widespread use of platforms such as Facebook, Google and Whatsapp, especially as it has increased in the context of the lockdown and remote working.

Respondents raised growing concerns about the involvement of third parties and private actors in non-enforcement aspects of immigration. These included:

- A wide range of apps providing right to work checks such as Experian, KPMG, PWC, etc.[13] – there is still little understanding about how these apps protect personal data; the data sets against which immigration checks are made and the relevant algorithm, as well as procedures for redress;

- Health apps such as Babylon Health[14] that use algorithmic decision-making;

- The use of TransUnion – by local authorities to conduct checks for the provision of child support;[15]

- Visa processing companies – concerns are being raised about their data processing practices, the training of staff and how are decisions made and specifically for family reunion visas.

3.3 Use of tools

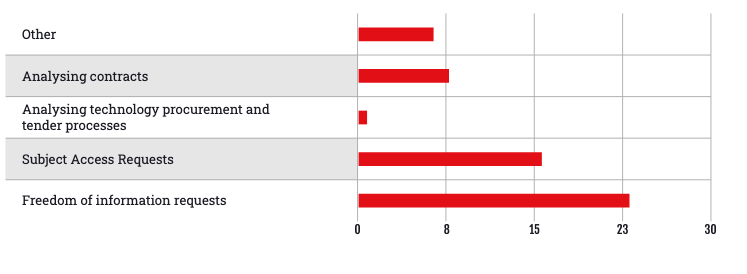

In terms of tools most often and confidently used in the context of their work, 23 respondents mentioned Freedom of Information (FOI) requests – and 16 mentioned Subject Access Requests (SARs). Six respondents mentioned having experience with analysing technology procurement and tender processes and only one mentioned experience analysing contracts. Most of those who had experience with FOI and SAR felt confident in their own abilities to use these tools. In analysing tenders and contracts more than half felt not at all or only slightly confident. In addition, one respondent mentioned their experience in analysing data sharing agreements.

Chart 1. Main tools used by respondents in their work (all that apply)

3.4 Needs and priorities

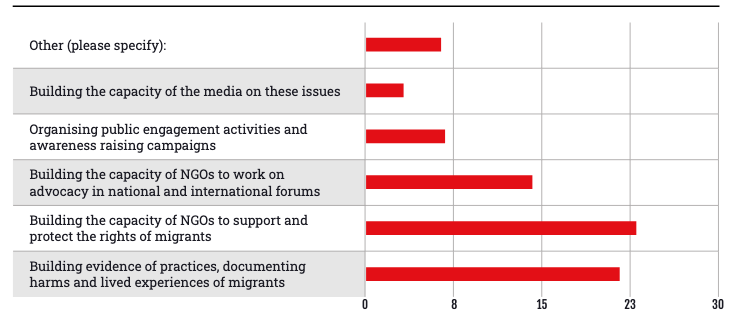

The main priority areas for the sector, based on the survey responses are:

- building the capacity of NGOs to better support their clients

- building the evidence base and documenting harms and lived experiences of migrants to engage in policy making and

- building the capacity of NGOs to raise awareness among the general public, national and international forums and engage in successful advocacy.

Organising awareness-raising and public engagement campaigns and building media capacity to cover these issues received much less support.

The priorities reflect the level of development in the sector where the focus is on building capacity to support clients, as well as engaging in policy and advocacy work.

Chart 2. Most urgent areas of work for the immigration sector on data exploitation and surveillance in immigration enforcement and protecting the rights of migrants (Responses include up to 3 options)

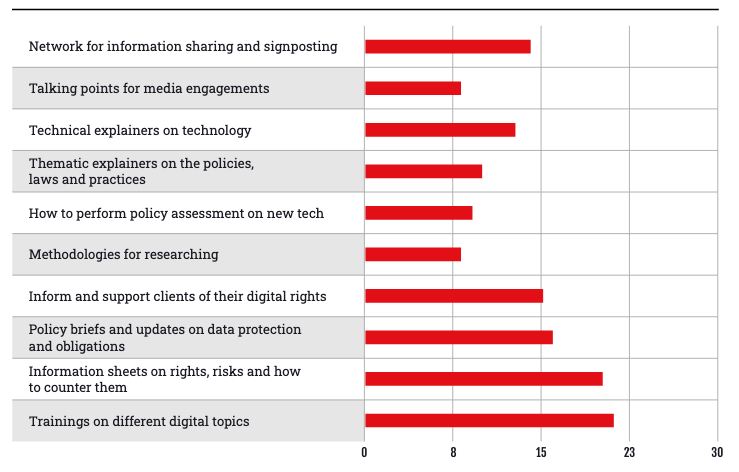

Asked about the types of support needed over half of the respondents expressed the need for trainings, information sheets on rights, risks and how to counter them, policy briefs on data protection and the obligations of government and the private sector and support for advising clients on their digital rights and how to safeguard them. Fewer respondents (8-13) indicated an interest to delve deeper into the development of research methodologies, policy assessments, thematic explainers on policies, laws and practices and technical explainers of new technologies. Nearly half of respondents expressed interest in developing a network for information sharing and signposting.

Chart 3. Type of support respondents would like to receive

A deeper look in the responses reveals that service delivery organisations and also organisations based outside of London are more interested in capacity building than support. Campaigning and policy organisations have expressed an interest into engaging on policy, law and practices, building technical capacity and media.

In terms of communication, the majority of survey respondents mentioned an interest in being part of a dedicated mailing list or a newsletter, as well as having a list of available resources and an ad hoc advice/ referral service and consultancy or access to tech advice. In terms of the regularity and intensity of communication respondents felt that communication once every 2-3 months or whenever there is a new development will correspond to their needs in this moment in time.

A summary of the main findings of the survey reveal a sector that broadly recognises the importance of new tech but largely lacks the framework to engage in a more systematic way. This concerns both the provision of support to clients, as well as engagement on new policy development and campaigning.

4 NEXT STEPS

The areas outlined below do not necessarily pertain to any specific organisation but rather suggest that working on them from different perspectives, mandates and expertise increases the capacity of the whole sector with the goal of further developing this ecosystem. Based on analysis of the responses provided below, we outline a number of areas for future work.

There is a clear need to support small service providers and community support organisations with little or no additional burden on staff

and time. This will include working with existing groups of organisations and with coordinators of such groups and networks; reflecting on the work they already do and the support they provide but do not necessarily see in terms of digital and data rights; providing accessible and tailored training corresponding to the specific needs of service providers; easy sign-posting and references. Also accessibly address privacy concerns arising from remote working and the implications for storing and accessing client data, as well the risks associated with different online platforms.

Work alongside organisations that provide direct support to clients – migrants and refugees to produce information sheets about existing privacy and data protection rights in an accessible form.

We identified that priority areas for trainings as:

- Data protection inside organisations

- Privacy and data protection in the immigration system and how to support clients

- Tenders and contract analysis

- Oversight of services outsourced to third parties or private actors.

Training modules can be developed and delivered jointly with other privacy and data protection organisations on the basis of their strengths and areas of expertise.

There were four medical organisations that all provided responses to the survey showing more than the usual interest. This can be attributed to the work already done in the context of opposing the data sharing agreement between the Home Office and the NHS, through which a number oforganisations have already developed capacities in understanding how data-sharing works and have experience in resisting this in the area of healthcare. There is scope to build on and deepen this effort and work with medical organisations to develop tools and materials on how to talk to patients and clients about data concerns.

Growing concerns and gaps in knowledge about how third parties and private actors are involved in immigration and how they can be held accountable can be addressed in two ways. On the technical level, conduct a technical analysis of the apps with the aim of understanding the data sets that underpin those services, the algorithms used and redress procedures and share the learning from this with service providers and their clients.

On a policy level support building the capacity to hold private actors accountable through tools such as Subject Access Requests and contract and tender analysis and through better understanding of the role of and how to engage with key actors in the area of data protection such as the UK’s Data Protection Authority, the Information Commissioner’s Office.

Based on the improved understanding of the problems associated with private and third-party actors, develop a joint campaign with interested migrant, refugee and data protection and privacy organisations to increase awareness and build resistance to the process of outsourcing immigration decisions to private actors.

To keep abreast of government developments and help sign-posting and sharing of information, as well as facilitate joint policy and campaigns initiative develop a network of digital rights and migration organisations. For organisations with policy and campaigning capacity, the network will provide opportunities to take joint action, such as the Open letter on NHSX App Safeguards For Marginalised Groups.[16] Interested migration and data experts and academics can also be part of the network, as can, most importantly experts with on the ground experience, whose contribution will ensure the debate is representative of the needs of people going through the immigration system.

Some organisations have responded that they do not have the capacity to be involved at all. For such organisations ad hoc sign posting and support can be made available, as well as a pool of resources and reference material, which they can turn to when their resources allow and interests align.

The importance of digital privacy and technology in the future of immigration policy cannot be underestimated, as well as the importance of increasing the capacity of organisations to engage with it. An emerging ecosystem of digital and migrant and refugee supporting organisations is working to better understand how new technologies and data are being used in immigration policy, to develop strategies for resisting these changes, and to better support individuals.

1 The existing data sharing agreements are described in detail in the report Care Don’t Share, published by Liberty in December 2018: https://www.libertyhumanrights.org.uk/ issue/care-dont-share/

2 Windrush Lessons Learned Review, Independent Review by Wendy Williams, March 2020: https://assets.publishing. service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/874022/6.5577_HO_Windrush_ Lessons_Learned_Review_WEB_v2.pdf

3 Open Rights group on the use of immigration detention: https://www.openrightsgroup.org/press-releases/ controversial-immigration-exemption-used-in-60-of-cases- court-case-reveals/

4 Open Rights Group on the NHSX data app and the hostile environment: https://www.openrightsgroup.org/blog/ hostile-environment-may-stop-migrants-from-using-nshx- tracker-app/

5 Runnymede, From Expendable to Key Workers and Back Again: Immigration and the Lottery of Belonging in Britain, Chapter 7: Organising against data sharing, Gracie Mae Bradley, p.33: https://www. runnymedetrust.org/uploads/publications/pdfs/ ImmigrationAndTheLotteryOfBelongingInBritain.pdf

6 Migration sector – needs and capacity assessment survey – preview https://www.smartsurvey.co.uk/s/ preview/O150PS/B546790E4FB7AF7AE6A462D7A99BB8

7 We have decided to keep the answers as they represent different parts of the organisation and work

8 Respondents gave more than one answer on this question

9 Respondents were asked to tick all that apply

10 JCWI and Foxglove have won a challenge over the use of a discriminatory algorithm for visa applications used by the Home Office: https://www.foxglove.org.uk/news/home-office-says-it-will-abandon-its-racist-visa-algorithm-nbsp-after-we-sued-them.

11 Privacy Internation released recently an important review of the use of social media monitoring by some local councils in England in decisions for welfare benefits and support: https://privacyinternational.org/explainer/3587/use-social-media- monitoring-local-authorities-who-target

12 Automated facial recognition technology used by police in South Wales challenged in court for having a “racial bias”:https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jun/23/uks-facial-recognition-technology-breaches-privacy-rights

13 Right to work apps: https://www.experian.co.uk/assets/background-checking/brochures/right-to-work-checks-brochure.pdf https://www.pwc.co.uk/services/legal-services/services/immigration/right-to-work-app.html https://home.kpmg/uk/en/home/ insights/2016/03/right-to-work-check-employer-obligations.html

14 BabylonHealth app: https://www.babylonhealth.com/

15 TransUnion credit check app: https://www.transunion.com/

16 Open letter: NHSX App Safeguards For Marginalised Groups jointly signed by JCWI, ORG, Foxglove, Liberty and Privacy International: https://www.openrightsgroup. org/publications/open-letter-nhsx-app-safeguards-for- marginalised-groups/