Alphonso knows what you watched last summer

The New York Times has published a story about a company called Alphonso that has developed a technology that uses smartphone microphones to identify TV and films being played in the background. Alphonso claims not to record any conversations, but simply listen to and encode samples of media for matching in their database. The company combines the collected data with identifiers and uses the data to target advertising, audience measurement and other purposes. The technology is embedded in over one thousand apps and games but the company refuses to disclose the exact list.

Alphonso argues that users have willingly given their consent to this form of spying on their media consumption and can opt out at any time. They argue that their behaviour is consistent with US laws and regulations.

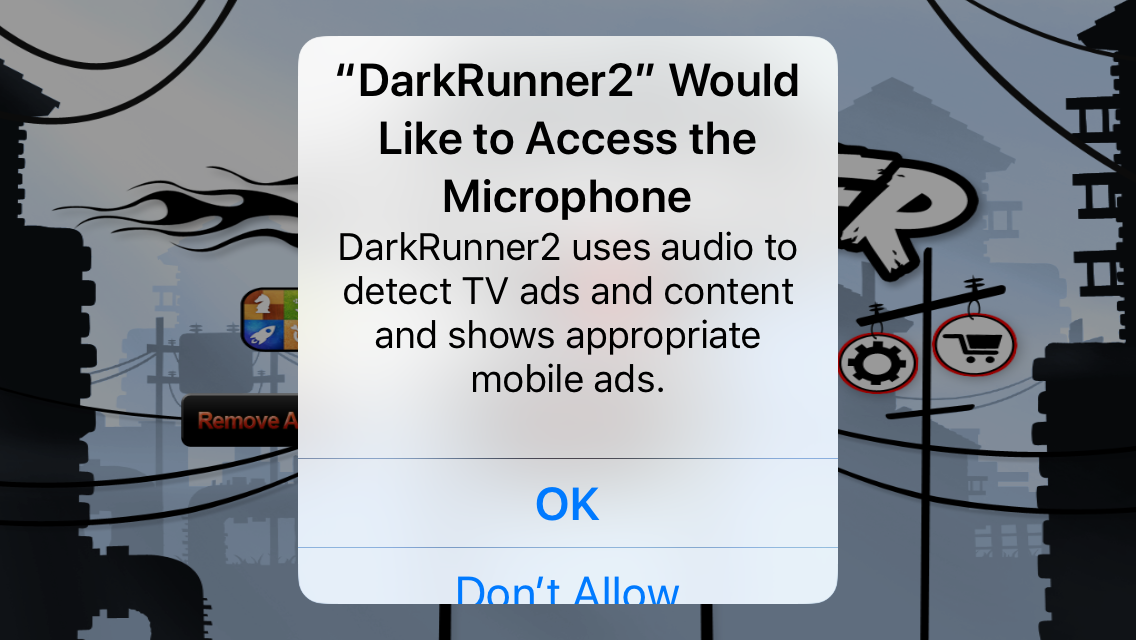

Even if Alphonso were not breaking any laws here or in the US, there is a systemic problem with the growing intrusion of these types of technologies that monitor ambient sounds in private spaces without sufficient public debate. Apps are sneaking this kind of surveillance in, using privacy mechanisms that clearly cannot cope. This is despite the apps displaying a widget asking for permission to use the microphone to detect TV content, which would be a “clear affirmative action” for consent as required by law. Something is not working, and app platforms and regulators need to take action.

In addition to the unethical abuse of users’ lack of initiative or ignorance – a bit like tobacco companies – there could be some specific breaches of privacy. The developers are clearly following the letter of the law in the US, obtaining consent and providing an opt out, but in Europe they could face more trouble, particularly after May when the General Data Protection Regulaiton (GDPR) comes into force.

One of the newer requirements on consent under GDPR will be to make it as easy to withdraw as it was to give it in the first place. Alphonso has a web-page with information on how to opt out through the privacy settings of devices, and this information is copied in at least some of the apps’ privacy policies, buried under tons of legalese. This may not be good enough. Besides, once that consent is revoked, companies will need to erase any data obtained if there is no other legitimate justification to keep it. It is far from clear this is happening now, or will be in May.

There is also a need for complete clarity on who is collecting the data and being responsible for handling any consent and its revocation. At present the roles of app developers, Apple, Google and Alphonso are blurred.

We have been asked whether individuals can take legal action. We think that under the current regime in the UK this may be difficult because the bar is quite high and the companies involved are covering the basic ground. GDPR will make it easier to launch consumer complaints and legal action. The new law will also explicitly allow non-material damages, which is possible already in limited circumstances, including for revealing “political opinions, religion or philosophical beliefs”. Alphonso is recording the equivalent of a reading list of audiovisual media and might be able to generate such information.

Many of these games are aimed at children. Under GDPR, all data processing of children data is seen as entailing a risk and will need extra care. Whether children are allowed to give consent or must get it from their parents/guardians will depend on their age. In all cases information aimed at children will need to be displayed in a language they can understand. Some of the Alphonso games we checked have an age rating of 4+.

Consumer organisations have presented complaints in the past for similar issues in internet connected toys and we think that Alphonso and the developers involved should be investigated by the Information Commissioner.