Analysis of proposed changes to the EU PSI Directive

The paper can be downloaded here

At the end of 2011 the European Commission presented a proposal for the review of the EU Directive on the reuse of public sector information (hereafter referred to as Commission’s Review) that updated the directive and strengthened certain provisions (1) .

According to the Commission’s communications, this revision has taken into account that since the original directive PSI has moved from a niche commercial sector to a central plank of digital transparency, e-government and open data innovation. The preparation phase included extensive consultation and several high quality reports.

Although a clear improvement, the proposed review fell short of unlocking the potential for public sector information to increase transparency, foster innovation, and improve European citizens’ lives. As we will see below, the demand for change evidenced in consultation responses is more far reaching than the eventually proposed changes (2). The revised directive is presented as part of a package that includes soft-law guidance to improve EU-wide consistency on aspects such as licensing. However, it appears that this policy model is already being challenged by various interests.

In March 2012 the Danish presidency of the Council prepared a new compromise (Danish Compromise), which contains some deep changes that could weaken the changes in the Commission’s text, and in some cases would seriously go against the spirit of the review (3).

This brief paper is not an exhaustive review of both documents, but an overview that presents the public interest advocacy of the Open Rights Group which we hope will help inform the UK position in the drafting of the final version of the revised directive. The following sections look at several aspects where we believe that the new texts could be improved to deliver the policy objectives of the Directive (4) :

- Prevent distortions of competition on the EU market: a level playing field re- users and incumbent hybrid public sector bodies engaging in commercial activities.

- Stimulate the digital content market for PSI-based products and services: several conditions regarding data re-use along the PSI exploitation chain, both commercial and non-commercial, must be fulfilled to stimulate economic growth and job creation through PSI re-use.

- Stimulate cross-border exploitation of PSI: A true, thriving internal market for PSI re-use will not emerge unless the regulatory and practical barriers to re-use across the EU are removed.

We wish to thank and commend the team at the UK Office for Public Sector Information for their exemplary behaviour in taking the time to engage with civil society. The UK government is leading on Open Data policies and we hope this translates into strong support for clear direction at the EU level. Also thanks to Raimondo Iemma and Katleen Janssen for providing feedback, although the opinions in this paper are exclusively ours.

1 Scope of documents

ORG’s view is that the Directive should apply as broadly as possible to public documents, both as a matter of principle and consistency, and because of the newer intention of the Commission to take a wider view from considerations of economic value towards democratic use of information.

The Commission’s Review extends the Directive to some cultural institutions: museums, libraries and archives, but not public broadcasters or educational establishments. There are no changes to the limits of the directive in terms of national security or commercial interests. This widening is welcome, but as we will see below cultural institutions are given too many special dispensations that weaken the practical impact of their inclusion. There are concerns as well that the newer amendments in the Danish Compromise could narrow the applicability of the directive.

1.1 Accessible documents

The new directive attempts to provide stronger provisions for reuse and ostensibly tries to close the gap between right of access and the right to reuse, without attempting to interfere with national laws on access to documents. This is made more explicit in the newer amendments in the Danish Compromise to Article 1 specify the applicability of the directive to generally accessible documents.

Subject to paragraph 3 of this Article, this Directive shall apply to generally accessible documents.

Article 3 in the Danish Compromise also adds the accessibility criteria (underlined below), which could be mis-interpreted as a narrowing of the scope of the Article:

(1) Subject to paragraph (2) Member States shall ensure that generally accessible documents referred to in Article 1 shall be re-usable for commercial or non-commercial purposes in accordance with the conditions set out in Chapters III and IV.

Accessible is defined in Article 2 in relation to national rules of access to documents:

Generally accessible documents are documents accessible under the national rules on access to documents.

With some extra information in Recital 7:

(…) where access does not require the demonstration of any specific individual interest, and documents that public sector bodies license, disseminate or give out.

The mention of published documents is welcome and should ensure that the new right of access criteria is seen in addition and not as substitute of the older criteria in the 2003 version, which focused on documents that were made publicly available in a proactive manner. For example, in the UK documents that have been – or are going to be published are not accessible under FOI.

While generally these new criteria should be an improvement in widening the scope of documents, the implementation of the Directive should ensure that public bodies in countries with weak access to information laws do not use this criteria to restrict re-use to a narrower set of documents than those previously reusable in relation to the public task. Not all EU countries have similar access to information legislation (5).

There are also questions in relation to the applicability of access regulations other than Freedom of Information laws, such as specific norms for public registers, cadastre, etc. – which may be narrower or in other cases broader, such as environmental information regulations.

1.2 Commercial confidentiality

In all versions of the Directive, Article 2 contains a complete exemption on grounds of commercial confidentiality. However, there could be room for a right to reuse certain documents from private organisations performing a public task on behalf of the state. This would provide a more future-proof directive as a mixed public-private delivery model for public services becomes widespread. There are similar changes being proposed in UK Freedom of Information legislation. Article 2 could be thus amended:

(7) generally accessible documents means documents that are accessible under the national rules on access to documents. This includes, where applicable, documents held by private organisations carrying out a public task.

1.3 Cultural bodies

The extension of the directive in the Commission’s Review to certain cultural institutions museums, libraries and archives is very welcome.

However, it would have been better to also include public broadcasting bodies, as the these are increasingly repositories of the collective memory in the same way as traditional archives, and already have materials coming into the public domain.

Despite the positive broadening of scope, we have found problematic the possibility for excessive and arbitrary restriction of cultural documents provided in the new Directive. The original 2003 Directive did not contain a strict obligation to allow re-use of all public held documents. The Commission’s Review in Article 3 removes the clause where the re-use of documents is allowed for general PSI documents, but leaves this caveat in relation to cultural materials. This appears to be a potential loophole, although it could also be interpreted to work in relation to restrictions from third party intellectual property or other external factors prevalent in the cultural sector.

This ambiguity is removed in the Danish Compromise, which rephrases Article 3 whereas the Directive would only apply to cultural documents

where the rightholder re-uses them or allows their re-use.

This appears to provide a clear mechanism for cultural institutions to narrow the accessibility criteria, as it would be easy to argue that most materials in museums, libraries and archives are accessible and therefore potentially re-usable. The new directive attempts to clearly widen the scope and drive public bodies to allow reuse as default. In contrast to other publicly funded bodies, cultural institutions are given too much control to decide where they allow re-use, which would likely restrict the availability of cultural PSI.

This restriction would also weaken in practice the demand aspects of PSI. Article 4 of the directive states that public bodies should process requests for re-use, but cultural institutions would only apply the PSI directive to materials they have already marked for re-use, or are re-using themselves.

Although re-use is not defined and it is probably the wrong terminology, as holding institutions are generally first users we can interpret it here as covering materials that either have been put online or that generally have already been digitised (6). This will be positive in relation to works already digitised, as they would be automatically covered. However, this definition could also curtail demand driven digitisation until institutions come up with some plan for digitisation in their own terms. Only around 11% of European cultural heritage has been digitised (7).

The revised Directive should apply to the full extent possible to cultural materials along the lines established for other public sector bodies, within the parameters established elsewhere in the text of respecting intellectual property, etc.

There is a particular issue with public domain materials. Any documents where the author’s copyright has expired are in the public domain, so the holding institution is no rightholder, but a custodian. The new Directive should make clear that public domain documents must be automatically reusable. We could add to recital 7a:

Documents in the public domain held by libraries (including university libraries), museums and archives will be presumed to be reusable.

1.4 Privacy and data protection

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has recently issued an opinion (8)raising concerns in relation to the revised PSI Directive and associated Open Data initiatives. The opinion provides a detailed analysis covering many important aspects ranging from licensing, anonymisation and transfer of data outside the EU.

Most of these issues have to be incorporated in the soft law measures but some affect the revised Directive. ORG would agree with the EDPS that the Directive should be amended to establish more clearly the scope of applicability of the PSI Directive to personal data.

2 Formats

ORG believes together with the majority of respondents to the public consultation that PSI should take full advantage of contemporary web technologies and therefore should be presented in machine-readable formats. This updates the terminology of the previous directive, which referred to electronic means. In addition, we believe that the best way to preserve interoperability and a healthy open market is to use open standards.

2.1 Machine readability

The Commission’s Review contains clear direction for machine readable data, instead of in electronic format, with the Danish Compromise providing a minor tweak:

1. Public sector bodies shall make their documents available in any pre existing format or language, and, where possible and appropriate, in machine-readable format and together with their metadata through electronic means where possible and appropriate. This shall not imply an obligation for public sector bodies to create or adapt documents in order to comply with the request, nor shall it imply an obligation to provide extracts from documents where this would involve disproportionate effort, going beyond a simple operation.

There are obvious concerns about costs. However, while we have to be realistic about not putting an unreasonable burden on pubic bodies, this formulation is not tight enough and could have limited impact to increase machine-readable information.

The cost of adapting legacy documents is not trivial, but there could be a stronger presumption for machine-readable delivery with exemptions where costs are deemed too high following a transparent process along the lines of the criteria for higher charges. In any case there should be a strong obligation in relation to newly created documents. Demystifying machine-readability and explaining its importance for digital re-use may be important, as some opposition to these measures could be based on erroneous assumptions about costs and complexity.

In any case, machine readability should complement -not substitute information that can be directly used by citizens, who should be able to chose the best way to receive it.

2.2 Open Standards

The Directive should ensure that PSI is delivered in formats that do not promote monopolies or impede interoperability and cross-European collaboration. The use of open standards is the best way to achieve these aims. The communications around the Commission’s Review explain that the Commission believes that this aspects are best left to soft-law co-ordination. We think that implementing consistency without a stronger legal element will be very difficult.

The use of open standards should extend to licensing in order to avoid complex legal processes. Some countries, such as UK, are using Creative Commons compatible licenses and imparting a level of consistency.

Implementing both concerns, Article 5 could read:

Public sector bodies shall make their documents available in any pre existing format or language, and where possible and appropriate, in a machine-readable format based on open standards, together with their metadata. Documents created after entry into force of this Directive shall in principle be made available in machine readable format. This shall not imply an obligation where the adaptation of existing documents, including the provision of extracts, would involve disproportionate effort, according to transparent, objective and verifiable criteria.

3 Charges

ORG supports free open data both for commercial and non-commercial uses in order to promote widespread innovation.

The Commission’s Review makes marginal cost charging the default for PSI (Article 6), displacing the cost-recovery charging model of the 2003 Directive:

Where charges are made for the re-use of documents, the total amount charged by public sector bodies shall be limited to the marginal costs incurred for their reproduction and dissemination.

3.1 Free open data and marginal costs

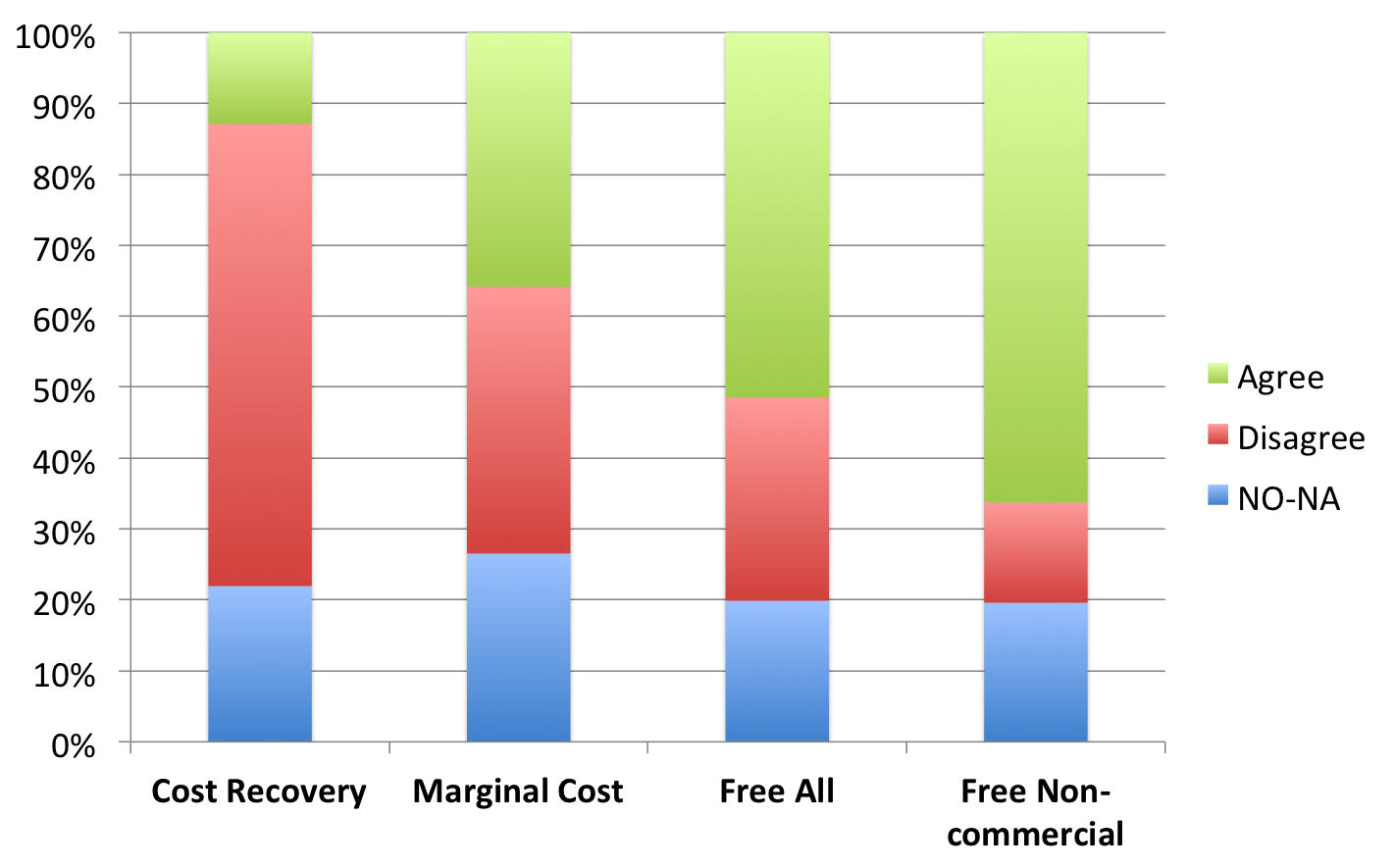

While marginal costs are a positive step, the majority of the respondents to the EU consultation supported some form of free data, as we can see in this simplified chart based on the responses:

This simplified chart groups together the various options for cost recovery (3) and marginal cost (2) respectively, the No Answers together with No Opinion, and the different degrees of support or rejection (strongly/normal) for each position. For the detailed figures behind it see the full stakeholders report referenced above.

Marginal cost pricing appears to be less supported and also less understood, with 25% of respondents not having a firm opinion. If such numbers are not clear about marginal costs, implementation could be problematic.

The main study used by the Commission to prepare these changes (POPSIS) (10) looks at low or zero charging, but does not provide sufficient distinction between these. These two pricing strategies may be interchangeable for an analysis of reuse at macro level, but any charges clearly have an impact on the development of free non-commercial reuse services, for example by civic organisations. In some cases the latter might be able to subsidise or pass on the low marginal cost charges to end users, although they may not be able to close gaps in cash flow.

However, many non-profit projects providing free open data are not able to track further reuse. Pricing out civic reuse through marginal cost charges would reduce the scope for mediation of public information to citizens, thus possibly reducing the diversity of viewpoints required for a healthy democratic process. We can also examine whether if marginal costs are low enough not to have an impact on re-use they may not have a great impact on the public purse, and in most cases could be subsidised.

As we saw above, the objectives of the Directive include stimulating non-commercial re-use, but this would be particularly affected by charges. Applying a separate criteria to non-commercial re-use would create a new set of problems in trying to define exact boundaries and would discourage hybrid models and social entrepreneurship. Therefore we would propose that free data should be the default model.

Article 6 could read:

Documents will be made available at zero cost wherever possible. Where charges are made for the re-use of documents, the total amount charged by public sector bodies shall be limited to the marginal costs incurred for their reproduction and dissemination.

3.2 Weakening marginal cost charges

ORG would hope to see charging exceptions becoming rarer and mainly used as a transitional measure while alternative funding becomes available, but we can see the need for some flexibility. The Danish Compromise weakens key provisions in the regime of exceptions to marginal cost pricing.

The Commission’s Review provides for exceptions to marginal cost charges under fairly clear criteria:

- required to generate substantial part of operating costs

- in relation to performing public task

- through exploitation of intellectual property

- under objective, transparent and verifiable criteria

- public interest test

- subject to approval of independent authority

However, the Danish Compromise allows overcharging for bodies that are required to do so:

Paragraph 1 shall not apply to the following:

(a) Public sector bodies that are required to generate revenue to cover a substantial part of their costs relating to the performance of their public tasks,

(b) Libraries (including university libraries), museums and archives.

The amendment removes the need for objective, transparent and verifiable criteria, external approval and public interest test, in a serious weakening of the principle of marginal cost pricing. This would allow institutions and incumbent re-users that are currently benefiting from high charges, including entry barriers, to carry on business as usual. This would undermine the policy aims of the Directive to reduce market distortion by creating a level playing field for newcomers.

The new amendments also remove the connection with intellectual property, or even data, so it could open the way for all sort of costs to be used to justify higher charging. There are some provisions for Transparency in Article 7, including the charging process, but these would not constrain charges over marginal cost, only provide an explanation of what factors will be taken into account.

These amendments in the Danish Compromise should be removed.

3.3 Cultural institutions exemption

The revised directive extends its coverage to cultural institutions museums, libraries and archives but it gives them a blanket exemption to marginal cost pricing, where they are allowed cost recovery plus a reasonable rate of profit. This exception in principle relates to the need for investments on digitisation. The reality of digitisation is more complex and involves widespread financial cuts combined with a lack of vision for the digital transition among many institutions and cultural policymakers. This means that in many cases digital assets are perceived as potential revenue in a way that fundamentally conflicts with the spirit of the directive.

Cultural institutions should be brought fully in line with other public bodies, with clear criteria and oversight for charging policies. This would allow them to justify overcharging if they truly required to cover costs for digitisation or any other operational costs. There is no reason for a blanket exemption, which will only hamper widespread re-use of low value cultural works, and serve to delay the exploration of alternative business models. Paragraph 3 in the Commission’s Review should be removed to leave cultural institutions under the general regime of exceptions.

- Notwithstanding paragraphs 1 and 2, libraries (including university libraries), museums and archives may charge over and above the marginal costs for the re-use of documents they hold.

If this is not possible in the current policy context, at the very least there should be a basic monitoring by the independent regulator of charging policies and their impact on re-use, and some review mechanisms.

4 Exclusive arrangements

The Commission’s Review maintains the general prohibition of exclusive arrangements, but unfortunately it also maintains the same regime of exceptions.

4.1 Whose public interest?

The Commission’s Review maintains the general principle against exclusive arrangements but adds some new clauses in relation to cultural bodies.

The re-use of documents shall be open to all potential actors in the market, even if one or more market players already exploit added-value products based on these documents. Contracts or other arrangements between the public sector bodies holding the documents and third parties shall not grant exclusive rights.

The general prohibition of exclusive arrangements for reuse in Article 11 contains a clause for exceptions in the public interest.

However, where an exclusive right is necessary for the provision of a service in the public interest, the validity of the reason for granting such an exclusive right shall be subject to regular review, and shall, in any event, be reviewed every three years. The exclusive arrangements established after the entry into force of this Directive shall be transparent and made public.

ORG believes that this review process could be an opportunity for introducing stronger exceptionality clauses along the criteria required for charging above marginal cost. This means adding to the public interest test the onus to present a case with objective, transparent and verifiable criteria, and approval by an external body.

Many existing PSI exclusive arrangements come under attack from other potential re-users, thus bringing into question the existence of a market-failure in the provision of a public good that would justify the exclusivity exception. The provision for reviews is important but without stronger criteria it is difficult to challenge these deals.

The recitals in the Danish Compromise give as an example of public interest a case where no commercial publisher would publish the information. This would appear a very low threshold for public interest, as there could be non-commercial publishers or citizen groups that could make use of the information. Therefore the Directive should enforce stricter requirements for exceptions.

However, where an exclusive right is necessary for the provision of a service in the public interest, the validity of the reason for granting such an exclusive right shall be approved by the independent regulator authority under objective, transparent and verifiable criteria. This decision will be regularly reviewed, and shall, in any event, be reviewed every three years. The exclusive arrangements established after the entry into force of this Directive shall be transparent and made public.

As the new directive clearly drives obligations for the wider availability of information while simultaneously limiting charges, it is very possible that some public bodies will try to discharge their new obligations by outsourcing under exclusive contracts rather than dealing with the added non-marginal costs.

Fundamentally, it seems that some public bodies have difficulties differentiating the public interest with their own interests as a publicly funded entity. The directive review process should help these organisations with clearer guidelines.

4.2 Exclusivity in cultural Public Private Partnerships

The introduction of cultural institutions under PSI has brought new challenges, as this sector has many existing exclusive arrangements, mainly as product of digitisation deals. The Commission’s Review gives a grace period of 6 years for existing exclusive deals with cultural institutions. However, the Danish Compromise brings new specific criteria for arrangements necessary to digitise cultural resources, which are limited to 7 years of preferential commercial exploitation without the need for review every three years that applies to other arrangements.

2a. Notwithstanding paragraph 1, where an exclusive right relates to preferential commercial exploitation necessary to digitise cultural resources, the period of such preferential exploitation shall not exceed in principal 7 years and need not be subject to review. The exclusive arrangements established after the entry into force of this Directive shall be transparent and made public.

At face value this is an improvement on the current situation, where such agreements tend to last for between 10 and 15 years. The figure of 7 years was recommended in the EU funded report by the Committee of Sages on digital culture The New Renaissance (11) – as an acceptable limit that balances commercial incentive with control by institutions. In many cases private public partnerships (PPP) are not just necessary for digitisation, but become part of the revenue structure of underfunded public institutions. The EU report on cultural PSI produced as part of the review states that generally these revenues are not required for the delivery of the public task, but they become important for the development of future re-use capacity. Therefore, the directive should introduce some criteria to establish necessity.

The one-size-fits-all 7 year limit may be required for simplicity, however there is a danger that instead of being an absolute upper limit, it becomes the norm. Current models based on yearly payments of a proportion of profits incentivise longer contracts. It would be preferable to set the duration of each agreement following a flexible mechanism based on transparent cost recovery plus reasonable profit. If the contract was loss making and the recovery plus reasonable profit was not forthcoming in the predicted number of years, the private partner could ask for an extension up to the maximum of 7 years.

There is another potential issue. Paragraph 2a refers to the period of preferential commercial exploitation, not the full duration of the arrangement, which in principle could be longer than 7 years. However, there are different clauses in some of these contracts, such as the Google Books deal with the British Library (12), that place other restrictions on the re-use of digital copies held by institutions not related to commercial exploitation, such as prohibiting free mass downloads. In such contract non-commercial text mining is allowed, but only after a separate arrangement is made with Google.

The directive should make clearer that after 7 years the institutions must be completely free to allow all forms of re-use of the digital copies obtained in the PPP deal, particularly if these are from public domain works.

2a. Notwithstanding paragraph 1, where an exclusive right relates to preferential commercial exploitation necessary to digitise cultural resources, the period of such preferential exploitation and any restrictions placed on the public body shall be calculated to permit recovery of the cost to the private party of digitisation and dissemination, together with a reasonable return on investment, and in principle shall not exceed 7 years. The exclusive arrangements established after the entry into force of this Directive shall be transparent and made public.

4.3 Sunset clause for cultural exclusive deals

The Danish amendment also changes the termination date for exclusive digitisation deals, where a new paragraph 3 in Article 11 now reads:

3. Existing exclusive arrangements that do not qualify for the exception under paragraph 2 shall be terminated at the end of the contract or in any case not later than 31 December 2008. However, such arrangements involving libraries (including university libraries), museums and archives that do not qualify for the exception under paragraph 2a shall be terminated at the end of the contract or in any case not later than 31 December 20XX [6 years after entry into force of the Directive].

where the Commission’s original review simply said:

However, such arrangements involving cultural establishments and university libraries shall be terminated at the end of the contract or in any case not later than 31 December 20XX [6 years after entry into force of the Directive].

We can see the difficulties in bringing to a closure existing PPP contracts, with the potential for litigation where the private partner has invested in digitisation, and that therefore the sunset clause would require some flexibility. As we mentioned before to the best of our knowledge in UK these contracts range from 10 to 15 years. However, a blanket exemption for all digitisation contracts is too blunt. The proposed 7 year limit is thought to provide a reasonable return of investment, and therefore it could be reasonable to assume that many existing deals could be shortened without making the private partner incur loses. A case-by-case approach would be better but in any case an absolute limit should be provided even if it is 10 years to avoid any loopholes.

In addition, this paragraph could be open to the interpretation that arrangements for digitisation do not need to be terminated at the end of the contract at all, in the same vein as the general public interest exception in paragraph 2. This should be clarified, as the rationale is different in that digitisation is a one off event, not an ongoing necessity to make the information available.

It would be preferable to say clearly that all existing cultural exclusive reuse contracts will have to terminate by the end of contract or 6 years, but that digitisation contracts where the private partner has invested will receive special flexibility to a maximum of 10 years. A new paragraph could be added

However, such arrangements involving libraries (including university libraries), museums and archives that do not qualify for the exception under paragraph 2a shall be terminated at the end of the contract or in any case not later than 31 December 20XX [6 years after entry into force of the Directive]. Existing exclusive arrangements that qualify for the exception under paragraph 2a shall be terminated at the end of the contract or in any case not later than 31 December 20YY [10 years after entry into force of the Directive].

5 Review, coordination and oversight

The Commission’s Review introduced stronger oversight and coordination, which ORG would support in principle, although as we said above we are sceptical of the efficiency of soft measures for coordination in terms of licensing and standards. The Danish Compromise however introduces several changes to the process which would have detrimental consequences.

5.1 Independent regulator

Article 4 in the Commission’s Review introduced a new layer of oversight:

The means of redress shall include the possibility of review by an independent authority that is vested with specific regulatory powers regarding the re-use of public sector information and whose decisions are binding upon the public sector body concerned.

However, the Danish Compromise removes the word regulatory which could mean in cases a toothless authority, as regulation is generally very well defined in law, as opposed to specific powers. This should be reversed.

5.2 Reporting

Article 13 in the Commission’s Review introduced a 3 year review calendar and yearly reporting obligations for member states on their progress. The Danish Compromise weakens these provisions by bringing a 5 year review with 2 year reporting.

The Commission shall carry out a review of the application of this Directive before 1 July 2008 [3 5 years after the transposition date entry into force] and shall communicate the results of this review, together with any proposals for modifications of the Directive, to the European Parliament and the Council.

Member States shall submit a yearly report every 2 years to the Commission on the extent of the re-use of public sector information, the conditions under which it is made available and the work of the independent authority referred to in Article 4(4).

Given the pace of change in this area it would appear that the increased costs of higher reporting frequencies would be justified. Changes should be reversed.

5.3 Soft law coordination

In recitals 17 and 18 the Danish Compromise introduces some changes deleting certain recommendations that would undermine the soft measures proposed by the coalition and further weaken the consistency of the application of the directive across Europe:

(1) It is necessary to ensure that the Member States (see recital 19) report to the Commission on the extent of the re-use of public sector information, the conditions under which it is made available, and the work of the independent authority. To ensure consistency between approaches at Union level, coordination between the independent authorities should be encouraged, particularly through exchange of information on best practices and data re-use policies.

(2) The Commission should assist the Member States in implementing the Directive in a consistent way by giving guidance, particularly on charging and calculation of costs, on recommended licensing conditions and on formats, after consulting interested parties.

This would have a negative impact on the rationale presented by the Commission for combining top down legislation on general terms with soft measures around specific aspects such as technical formats and licensing, which were left for coordination and exchange of best practices.

The implementation of Open Standards for example has been left out of the Directive although there is widespread consensus in the Open Data community that it is best practice. The option of neither legislating nor coordinating would lead to a lack of consistency and undermine a key policy objective of cross-border exploitation of PSI.